After laying out my journey to graduate school, a few people asked me how it is that I ended up choosing Yale over the other very good graduate programs that had offered me admission. Now, my partner and I here at Gurufi / FourthWrite are putting together a series of posts and videos to guide you through the process of applying to graduate school from beginning to end, but since people have asked, I’ll use this opportunity to talk some about the end of the process, which is choosing your school. This post is mostly specific to doctoral programs, but much of the reasoning is applicable to Master’s programs, professional schools (med, law, biz, etc.), and even to some extent to undergraduate schools.

To recap, I had been accepted into most of my top programs: Yale, Berkeley, Columbia, Harvard, UCLA, and Michigan. This left me in an envious -and given my previous application disasters, quite unexpected- position: which one to choose? It basically came down to five factors: fit, money, advisor, place, and placement.

1. Fit. This one is, really, the most important one. There are some objective ways to assess this, such as whether the program is strong in your particular field, the number of strong frequently-cited publications related to your topic that the department is churning out, etc. But, if we’re being honest, this was mostly a matter of the vibe. Unlike some professional schools (notably, medical school and business school), for the most part interviews play no role in doctoral program admissions, so I only visited these schools after I had gotten in. It’s a squishy metric, but in talking to students and faculty, I liked the “vibe” at Yale, Columbia, and Cal-Berkeley. I will still remember that, after an hour talking to a famous history professor at Cal, he said, “oh my god, I haven’t filled out my bracket! Are you an NCAA hoops fan!?!?” I was, so the two of us spent the next 25 minutes talking college hoops as he filled out his bracket. I thought, “I could go here.” This may seem irrational, but the average PhD program takes 7 years, so you will be spending A LOT of time with these people, so you’d better make sure that you could like them.

2. Money. When I decided to pursue a PhD, my rule was that if a school wasn’t going to fund me fully, I would consider it a rejection. Earning a PhD is hard, and I didn’t want to weigh down my studies with concerns about racking up more student loan debt. As a practical matter, all of the top private schools (Ivy Leagues, Stanford, Duke, Northwestern, etc.) fully fund all of their PhD students with grants and stipends. To be admitted is to be admitted with tuition waived plus a small allowance for living expenses (this year, Yale’s stipend is about $31,000). In the good public schools (the UC system, Michigan, UNC, etc.) that’s not always the case. In fact, most of them will both push for you to pursue outside funding from fellowships and have heavier teaching requirements to pay your way through. As a point of comparison, my first two years at Yale I would not teach, whereas I was expected to be a TA right from my first semester had I gone to Cal-Berkeley. Teaching is a real time commitment, so it should factor into your decision.

3. Advisors. Getting the right advisor is huge. In fact, once you’re ABD (All But Dissertation, in the lingo), your advisor will be far more important to you than the program or the school. As such, I gave serious consideration to all of the people who might end up being my advisor at these various schools. (I’ll talk about this in a future post, but the funny and dirty little secret of PhD programs is that almost nobody studies the thing they intended to when they came, and thus you’ll probably not actually have the advisor you think. But still, this is an important part of the process) I talked to professors and asked them how their particular students did on the job market, and I also talked to current and former students about their experiences working with different professors. Were they supportive? Good mentors? Help provide them with structure and clarity? Etc.

4. The Place. Again, this often gets overlooked, but remember that you are going to spend A LOT of time in graduate school. So, if cities make you nervous and miserable, give very careful consideration before you go to Columbia or NYU, even if they are a better fit for you academically. Similarly, if college towns drive you nuts, and you need big city life, don’t go to Wisconsin because you’ll hate Madison. The truth is that if you are unhappy, the likelihood that you complete your PhD drops precipitously. There is no shame in saying that sunshine, weather, city size, culture, and other quality of life factors are important. If you catch yourself saying “it’s only 6 years, I can take it,” then stop and reconsider. It’s just not worth it, and your unhappiness could very well lead you to hate the subject you went there to study!

5. Placement. For all applicants, BUT ESPECIALLY FOR PEOPLE LOOKING TO GET INTO ACADEMIA, you should have a clear sense of what your job prospects are after graduation. Ask about recent placement success, talk to students about the support they get from the Career Development Office, and if you’re looking to go into academics, get a sense of where recently-minted PhDs have gone. If we’re being blunt, if your intention is to become a professor, then you really should think twice, then think twice more, before going to any program outside of the top 15 in your field. It’s hard for Harvard and Yale PhDs to get academic appointments, and it’s near impossible for a PhD from a less sterling university.

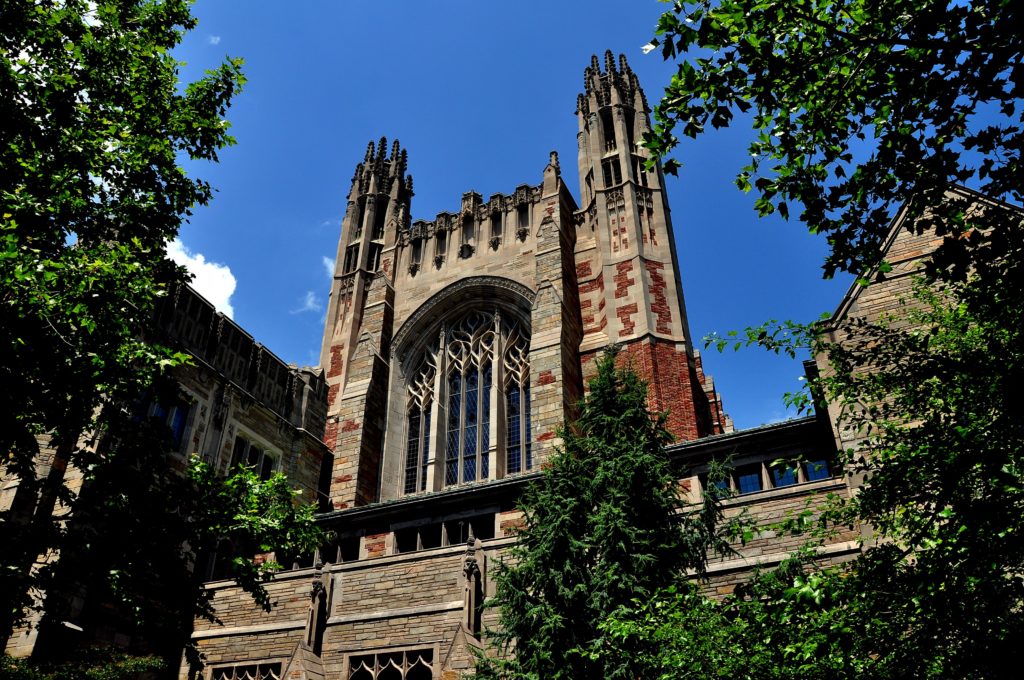

The reason that I ended up choosing Yale was because of reasons 1,2,3, and 5. Fortunately, I had close friends who were there, so Factor 2 ended up not being a big deal, even though (sorry) New Haven isn’t nearly as nice as Berkeley, New York, Boston, Los Angeles, or Ann Arbor.

In the end, I think that everyone who goes through this makes their own metric, but these metrics are mostly a way of getting at what you just know in your heart is true. In fact, even though I made myself a big fancy chart with all the pros and cons, I probably put my finger on the scale to get the outcome that my heart wanted anyway. And that’s okay. It worked for me: I had a great time in graduate school, made lifelong friends, got my PhD, and afterwards taught at Harvard before discovering that academia isn’t my cup of tea. The only thing that I would urge everyone to do is to be really thoughtful about ALL elements of a school. To me, it’s absolute folly to just accept years and years of misery to achieve some professional goal.

I guess that’s why I’m not a doctor.