If you are applying to a PhD program, it’s important to understand how the admissions process works once your application gets sent. Many people offering expertise on admissions writing come from the world of undergraduate, business school, or law school admissions, but these areas of expertise are of very limited usefulness when it comes to understanding how to approach an application to a doctoral program. To be blunt: while some basic concepts are portable, on the whole an admissions strategy built upon a business school or undergraduate model puts you at an acute disadvantage.

Below are four factors that will help you understand how to approach your graduate school application. For additional questions or to get help with your graduate school personal statement or positioning, be sure to check us out at Gurufi.

1. Professors are the AdCom. Unlike colleges, law schools, and business schools, graduate school departments don’t have dedicated staff whose only full-time position is selecting the incoming class. In most departments, the Admissions Committee is composed of professors in that department, sometimes supplemented by one or a few advanced graduate students or postdocs. As such, you can be assured that you are interacting with high-level experts who understand your subject with comprehensive sophistication and granularity. These means a few things: a) you can feel a bit more free to use jargon; b) you need to know the department’s strengths; c) you should figure out where your department’s professors stand on controversial topics within your field so that you don’t step on toes; and d) you need to write as though you understand the field yourself and are ready, on day one, to do advanced work within it. This last point is really vital. Unlike business school applicants, who don’t need to spend time in their essay discussing the scholarship on, say, leadership, investment, or corporate structures, you need to have at least a paragraph (and probably more) in your essay where you’re engaging with the core questions within the field you’re studying.

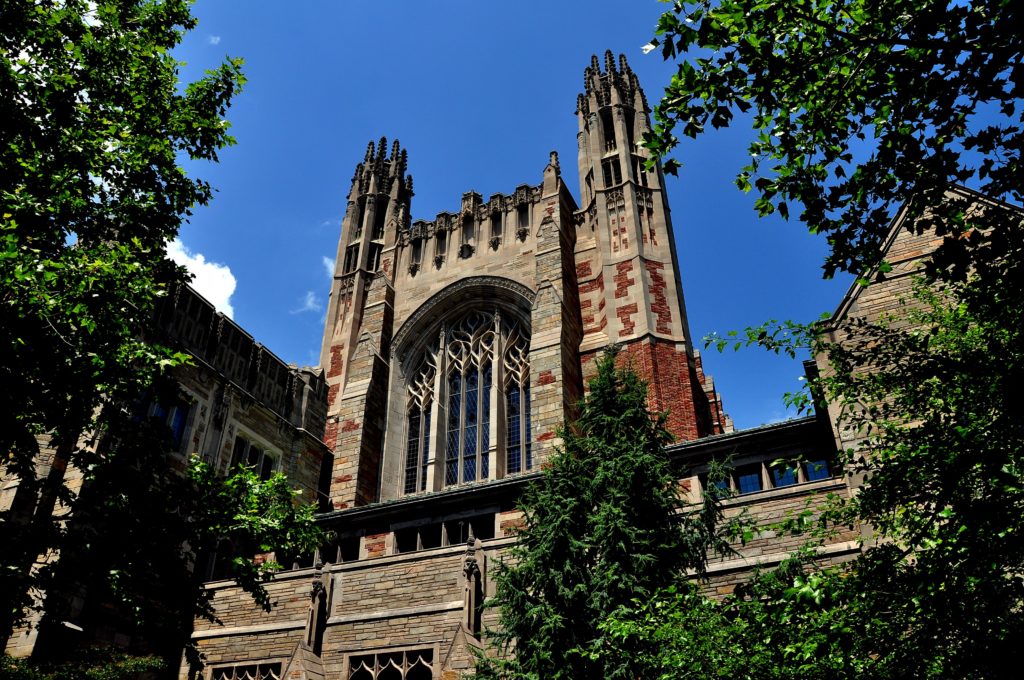

2. Grades are important, BUT… One of the things to keep in mind is that departmental admissions committees have a great deal of latitude to admit whomever they want. In fact, except in rare cases, the overall graduate school admissions boards tend just to rubber-stamp the choices made by particular departments. As such, particular departments don’t have concerns about, for instance, maintaining an overall GPA average for the admitted class; they just want to pick the best people who fit the culture and academic strengths. What this means is that, while grades are very important, they’re not the be-all and end-all of doctoral admissions. I recall one instance of a student, who is now a professor at a very prominent West Coast university who had a 1.8GPA in college, but went on to work as a lab tech where he fell in love with neuroscience and in his free time began studying up on the subject. A few years later, he was making substantive contributions to the research of the lab and his advisor urged him to apply for doctoral programs. His advisor wrote him a compelling letter of recommendation that detailed his accomplishments and, despite his disastrous four years of college, was admitted into a dozen of the top doctoral programs, including Harvard and UCSF.

Also, do keep in mind that many departments have different ways of calculating GPA. When I was on the Admissions Committee, we were given a form that included “relevant GPA,” which excluded any grades from the first 1.5 years of college. This is based on pretty sound research suggesting that grades in the first three semesters of a student’s undergraduate career are mostly correlated with the quality of their high school, and not long-term success or ability. This may have changed since, but when I applied to graduate schools, about half of the top programs either didn’t even ask my freshman year grades (there was no spot on the form for them), or I later discovered that the packets produced by the department secretaries simply excluded this information. This can be a huge relief to people who might have stumbled out of the gates but found their academic stride later.

3. The AdCom is very concerned about “fit.”

When the committee met, one of the most frequent conversations that we had about a candidate is whether they were a good fit. This is important for two different reasons. First, the AdCom wants to know if you will actually attend if admitted. Most graduate school cohorts are quite small (usually fewer than 25 people, often fewer than 10), and once admissions are offered, the tables turn a bit and it becomes a scramble for departments to recruit the admitted applicants they see as the top students. So, if the committee is confident you’ll attend, they’re slightly more likely to offer admission to you. This is doubly true if a school perceives that it’s your “safety school.” In my case, I was admitted into all of the top-8 programs I applied to, but didn’t get into the #24-ranked program. I don’t know for certain, but I think it was likely because the committee didn’t think I would go if offered a slot. With this in mind, if there is a school that is absolutely your top choice, say that in your essay or in other communications with the department. BUT, don’t say this to more than one school. First, it’s lying; and second, these professors talk to each other, and there’s a too-high-to-risk-it chance that your rouse will be discovered.

The other way that fit becomes an issue is in discussions about whether your intended area of scholarship actually fits in with what that department does. Note that this is partly linked to the discussion I just referenced, in that we often had conversations that went like, “Jane is interested in applied legal theory, but Stanford’s department is better at that. She’s likely to go there…” But, it was often just a more general assessment of where the candidate might fit in within the department. It’s important to note that sometimes this is a function of how many advisees the professor who would likely serve as your advisor already has.

4. Your potential advisors are consulted… If the committee looks at your application and says, “oh, Jane would likely work under Prof. Sarah,” then do note that Prof. Sarah may be contacted about your application. And, if you do mention (which you ABSOLUTELY should) a professor under whom you are interested in working, the committee will usually contact that professor about your application. Having them say, “yes, Jane’s ideas are interesting and I could work with her” is quite useful for your application. This is why it’s really important to contact your potential advisors before you apply (a VERY brief email + a request for a coffee or telephone call) so that they have the heads-up on your application. Sometimes, they might tell you that they’re not taking graduate students or that you’re not what they’re looking for. This can be disappointing, but it allows you to reframe your admissions strategy accordingly by either selecting other professors or simply scratching that school off your list.

You see that the admissions process for PhD programs is quite different than that used in law schools or business schools. There are additional steps that you need to take and additional things that you need to be cognizant of. It’s its own kind of process, and as such if you decide to get help with your application or with your personal statements, then you need to choose someone who’s aware of how this all works. At Gurufi, all of our consultants and editors have graduated from elite graduate programs and we have experience serving on graduate admissions committees so we know the idiosyncrasies of this process quite well.