Applying to doctoral programs can be stressful and mysterious, and one of the real challenges is that most of the advice that you’ll find online about the application process comes from people whose experience is in the world of business school, law school, or undergraduate admissions. This advice isn’t well suited to graduate school applications because the process is simply different, as are the goals of the admission committee and the people who staff that admissions committee. We detailed much of this in a recent blog post.

Today, I want to follow up on some of the items we talked about by giving you three practical tips that will help you with your PhD application.

1. It’s okay if you don’t know exactly what you want to study. In my last blog, I pointed out that, the closer you can get to articulating what the thesis of your eventual dissertation will be, the better. This advice often elicits two concerns from clients. First, will being overly specific hurt my chances of admission? No, quite the opposite. If you don’t have a really specific answer to “what?” and “why?” you’ll come across as someone who isn’t quite ready for graduate school. The old joke that ‘PhD’ stands for “Piled Higher and Deeper” is a reminder that doctoral studies are about becoming highly expert in a very narrow question within a very specific field. Or, as my old PhD advisor put it, “Brian, your task is to become the world’s foremost expert in the thing you’re writing about.”

Second, people are often concerned that they either don’t yet know what exactly they want to study or that they might change their mind along the way. Now, if you have no earthly clue whatsoever what you want to investigate, the short answer is that you have no business applying to graduate school. You should at least enter graduate school with some idea of what you want to study. BUT, even if you don’t, you should at least be able to articulate a plausible question that you may want to study. It’s fine if you end up changing your focus because most people don’t actually end up researching the precise areas that they intended to when they arrived. Now, obviously, you will stay close to home, intellectually speaking, so it’s not as though you’ll go from studying Medieval History to Cell Biology, but chances are that you might, for instance, go from studying how neural cell plasticity is impacted by traumatic injury to studying how neural cell plasticity might be involved in autism. It’s the same general subject, be very different questions. That’s a VERY normal thing to happen. In fact, your initial classes and (if you’re in the sciences) rotations through labs are designed to give you a broader exposure so that you can select a precise topic that interests you.

So, if most people end up changing their intended thesis, why do the admissions committees even emphasize your laying out your intended intellectual route? Two reasons: 1.) applicants who can articulate what they see as a cognizable and important question have done the requisite homework and thus demonstrated their seriousness, and 2) you are showcasing your ability to think and write about complicated questions within the field, and especially your capacity to position yourself vis-à-vis the important debates. This is very important skill in academics.

2. You HAVE to email the professors. So, technically speaking you don’t have to do this. Many people are admitted without having done so. That said, you really should do it. The reasons have mostly to do with the nature of graduate school and the nature of graduate admissions. Suppose, for instance, that you want to study Cell Biology under Prof. Jones at State University. In fact, the work she’s doing is what inspired you to study cell biology, her papers are groundbreaking, and her excellence and reputation are what State University’s Department of Cell Biology are built upon. Given this, you need to find out if it’s possible to study under her. She might, for instance, be retiring, moving to a new position at a new university, or may not be taking any more graduate students into her lab. You would thus be in a bad way if you showed up at State University to study under her, only to discover that Prof. Jones is now at Stanford! Or, she might tell you that she doesn’t think you’d be a good fit, and that if asked, she couldn’t enthusiastically support your application. This would hurt, no doubt, but it would allow you to adjust your application tactics.

This brings us to the second reasons. You should email potential advisors because, if you mention them in your personal statement, the admissions committee will usually forward your application to them and ask if they are a good fit for what they do. Them saying “yes” certainly doesn’t guarantee your admission, but either a “no” or an indifferent response will hurt you. As such, you should let that professor know who you are so that when they get that email, they can, “Oh Jennifer? She’s great, and I think she has some interesting ideas and could do great work in my lab.”

Just so we’re clear, if a professor hasn’t heard of you and the Admissions Committee asks them about you, they likely aren’t going to take a ton of time to look over your application at that point. Professors are very busy with other teaching, research, writing, committee work, etc., and they rightly don’t see it as their job to resuscitate your application because you didn’t bother to reach out to them before you name-dropped them.

So, how do you reach out to a professor? I’ll have more on this tomorrow, but the short version is that you should write a VERY short email introducing yourself, identifying what you’re working on, and asking if you could have 10 minutes of their time. Attach your CV and any relevant other documents. (Again, more on this tomorrow)

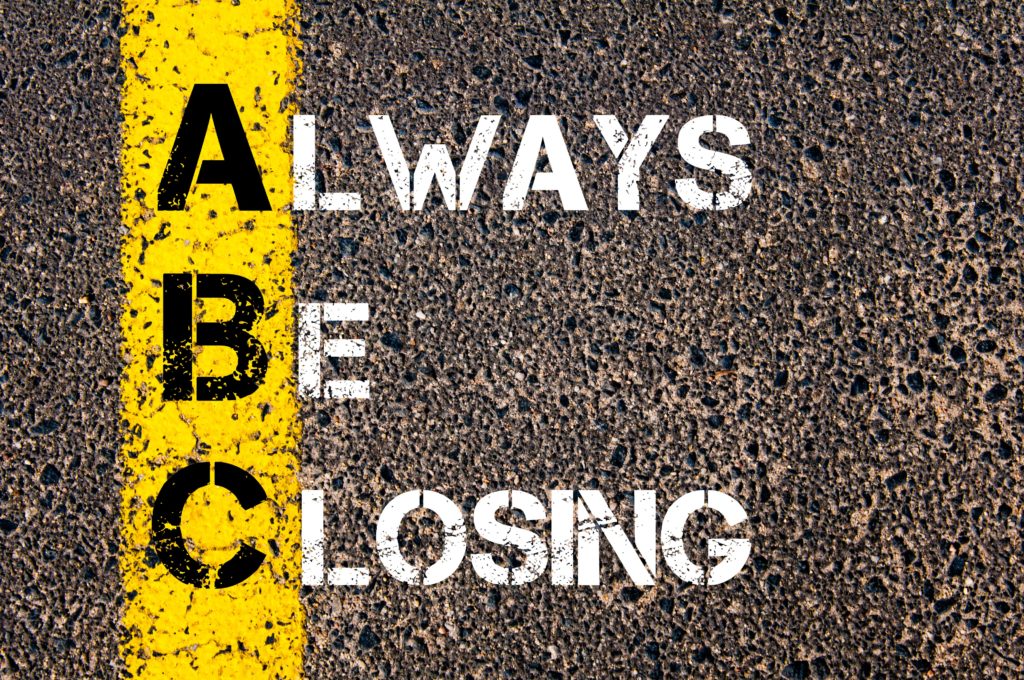

3. Copy-Paste will kill your application

We all know that applying to graduate school is hard and time-consuming. You have to study for the GRE, get letters of recommendation, write a personal statement, research and contact potential advisors, revise your writing sample, and fill out lots of other forms. BUT, one thing that will really hurt your chances is to use a personal statement that is very obviously just a single standard essay with the names of your various schools copy-pasted in. It shows that you haven’t done your research and aren’t particularly interested in that school. This doesn’t mean that you have to write completely different essays for each school. In fact, it’s usually the case that you can write your first essay for your first school and repurpose the first two-thirds for every school, and then the final third or so that focuses on your fit with the school you’re applying to can be written custom for each university. But readers know when they’re reading generic broadly-applicable text with the school’s name pasted in, and they don’t like it. So if you have a section like this, dump it and rewrite it:

I want to attend Stanford University because of its excellent faculty, abundant research resources, and the opportunity to work within a renowned university. I have looked at the Course Catalog, and there are many classes that fit my intellectual interests…

You could replace “Stanford” here with any top school, so you’re not really saying anything useful or demonstrating that you know anything about Stanford other than it’s a good university.

All three of these points make clear that a lazy applicant is probably going to be an unsuccessful one. Yes, it takes extra time to email professors, generate a plausible dissertation thesis, and write lots of unique text for all of your schools. But if you’re thinking about spending 7 years in graduate school, why wouldn’t you take an extra 10–12 hours to make sure that you are attending the right graduate school and are positioning yourself for long-term success and happiness?