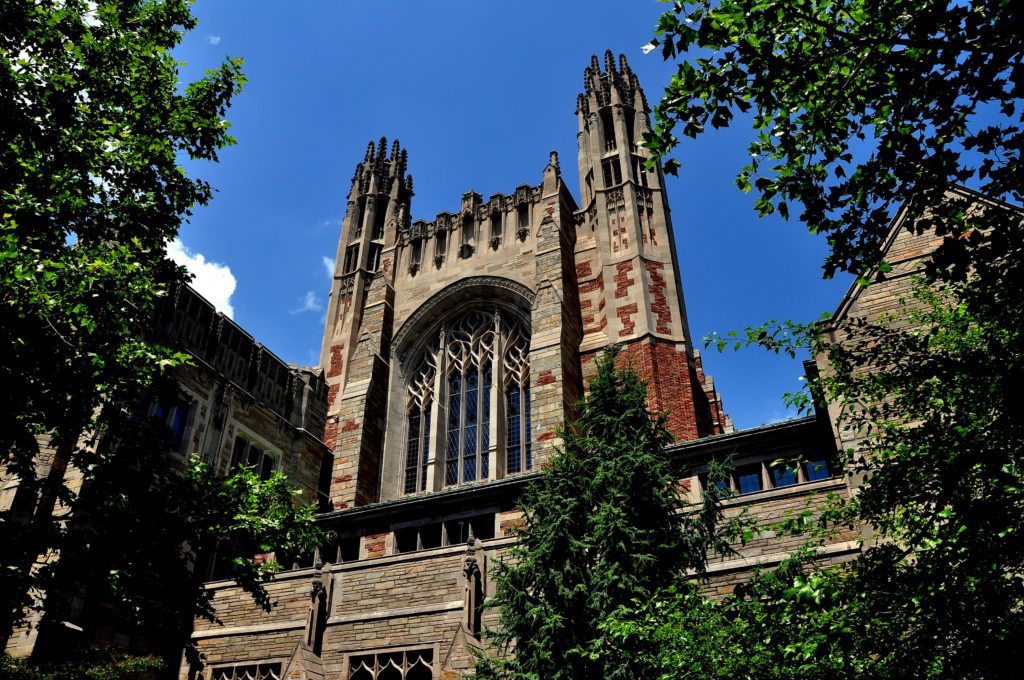

Some people perhaps thought my last post on academic life was too negative, so I want to provide some balance to people who feel passionately that they want to pursue a PhD but are also feeling a bit scared. Academia can be wonderful… or it can be hell. Knowing whether you’re cut out for it first is crucial. From bucolic afternoon strolls on lovely campuses to dedicating your life to studying and teaching ideas that you’re passionate about, the academic life is indeed attractive. Tweed jackets, coffee dates with smart people, getting paid to read books, and summers off—these are just a few of the myriad perks that make working as a professor one of the best gigs in the world. I spent six enriching years earning my Ph.D. at Yale, taught at Harvard, and still harbor immense affection for the time I spent in the hallowed halls of academia. Though I ultimately left for family reasons and a burgeoning business, I still miss it dearly.

Given my background, I am uniquely positioned to offer frank advice about pursuing a Ph.D. and embarking on an academic career. It’s a path marked not only by intellectual fulfillment but also by hard-earned successes and significant sacrifices. Here are 25 of the best aspects of life in academia, which might just sway your decision towards embracing this venerable path.

- Intellectual Freedom:Academia offers unparalleled freedom to explore ideas and arguments that fascinate you, without the direct pressures typical of corporate agendas. Yes, you have to navigate office politics and your arguments need to remain connected to evidence, but in the end you can pursue questions that fascinate, intrigue, or bother you.

- Passionate Peers:Surround yourself with people who are just as enthusiastic about your field as you are—a constant source of inspiration and challenge. If the phrase “nerd out” is something you use to describe yourself, then this may be the life for you.

- Impactful Research:Contribute to the body of knowledge in your field, impacting students, peers, and sometimes public policy. On the STEM side, all major practical advances have their roots in university research, so what you do to expand our collective knowledge can play a role in transforming the technology we use, the ideas that shape how we see the world, and the kinds of opportunities future generations have.

- Global Opportunities:Academic careers often come with opportunities to travel, study, and work abroad, enriching your personal and professional life.

- Academic Community:Belong to a community that values learning and scholarship, providing a supportive and stimulating environment.

- Lifelong Learning:Continue learning throughout your career, with access to cutting-edge research and ongoing professional development opportunities.

- Teaching:There’s a profound joy in teaching, in watching students grow intellectually and personally under your guidance. The relationships I built with students persists, and I remain in constant contact with many of them. Seeing them learn and grow has been a genuine blessing.

- Flexible Schedule:Though the hours can be long, they are often flexible, allowing you to manage your time according to your personal and professional needs. If you are a self-starter, this is ideal as you can shape your days, enjoy hobbies, and pursue family life.

- Tenure Security:Once achieved, tenure is a level of job security that is rare in other fields, allowing for risk-taking in research and stability in life.

- Sabbaticals:Regular sabbaticals allow for deep dives into research projects or a well-deserved break, something few other careers offer.

- Cultural Stimuli:Campuses are cultural hubs, offering access to talks, art shows, and other cultural events often free of charge. College towns often offer the best of big-city life with dining and cultural events that punch above their weight but green spaces, lovely houses, and small-town charm.

- Student Interaction:Engage with young, vibrant minds—students who can challenge and invigorate your own perspectives.

- Publishing:While challenging, the satisfaction of publishing research and advancing knowledge is immensely gratifying. There’s nothing quite like seeing your name on the spine of a book or having a paper you’ve spent years working on get published in a major journal.

- Academic Conferences:Participate in conferences that gather experts from around the world, offering networking opportunities and exposure to new ideas. I love conferences as spots to have intense-but-friendly (mostly) debates, meet up with old classmates, and gather with accomplished experts in their fields.

- Campus Amenities:Enjoy the beauty of campus environments, from libraries and labs to art centers and sports facilities. Saturdays at football games, visits to university museums, lectures by renowned experts and politicians in lovely auditoriums…

- Career Autonomy:Direct your own research, choose your teaching subjects, and guide your academic focus.

- Mentorship Roles:Act as a mentor to the next generation of scholars, guiding them through their academic and personal challenges.

- Research Funding:Access to research funding allows you to explore ambitious projects and collaborate across disciplines.

- Academic Recognition:Achieve recognition in your field, a testament to your contributions and hard work.

- Work-Life Balance:Academics often have the ability to balance work and personal life more effectively than many high-pressure professions.

- Inspiring Alumni:Connect with an extensive network of alumni who can open doors to various professional and academic opportunities.

- Technology Access:Use the latest technology and resources to further your research and teaching goals.

- Diverse Disciplines:Work closely with experts in a variety of fields, broadening your understanding and interdisciplinary connections. Though my field was in the humanities, I loved that most of my best friends were STEM professors. Hearing about what they did expanded my worldview in important ways.

- Creative Expression:Academic work often involves a significant amount of creative thinking and expression, whether in writing, problem-solving, or designing experiments.

- Sense of Purpose:Perhaps most importantly, academia offers a profound sense of purpose. Contributing to society’s knowledge and improving the lives of your students can be incredibly rewarding.

Choosing a career in academia is no small decision. It’s a path fraught with intense study, deep research, and a significant amount of uncertainty. For many, the allure of delving deep into a subject they love and contributing to our broader collective knowledge is compelling. However, the reality often differs from expectations. To truly understand if this path is for you, critical self-reflection is essential.

Next week, I’ll give my list of all the ways academic life is NOT great.

If you’re looking at grad schools and need help with your personal statement, CV, or writing samples, let Gurufi.com help. Our personal statement editors and consultants have decades of experience helping clients get into top Masters and Ph.D. programs in STEM, humanities, fine arts, and social sciences. Our specialty is helping you craft compelling personal statements that move the needle in your admissions process! For questions, shoot us an email at service@gurufi.com. Check us out on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.